May 28, 2003

A Masked Child Prays

A child prays for prompt end to SARS. Tzu Chis Chiayi Service Center in Taiwan organized the community prayer to encourage everyone to bring forth compassion and goodness through being vegetarian. As a vegetarian diet helps to purify our own thoughts, non-killing brings peace to society. 05/17/2003

May 27, 2003

Encryption and Wiretapping

writes in the May 15, 2003, CRYPTO-GRAM:

1) Encryption of phone communications is very uncommon. Sixteen cases of encryption out of 1,358 wiretaps is a little more than one percent. Almost no suspected criminals use voice encryption.

2) Encryption of phone conversations isn't very effective. Every time law enforcement encountered encryption, they were able to bypass it. I assume that local law enforcement agencies don't have the means to brute-force DES keys (for example). My guess is that the voice encryption was relatively easy to bypass.

In the long-titled "Report of the Director of the Administrative Office of the United States Courts on Applications for Orders Authorizing or Approving the Interception of Wire, Oral, or Electronic Communications," we find the following interesting quote:

"Public Law 106-197 amended 18 U.S.C. 2519(2)(b) in 2001 to require that reporting should reflect the number of wiretap applications granted in which encryption was encountered and whether such encryption prevented law enforcement officials from obtaining the plain text of communications intercepted pursuant to the court orders. In 2002, no federal wiretap reports indicated that encryption was encountered. State and local jurisdictions reported that encryption was encountered in 16 wiretaps terminated in 2002; however, in none of these cases was encryption reported to have prevented law enforcement officials from obtaining the plain text of communications intercepted. In addition, state and local jurisdictions reported that encryption was encountered in 18 wiretaps that were terminated in calendar year 2001 or earlier, but were reported for the first time in 2002; in none of these cases did encryption prevent access to the plain text of communications intercepted." (Pages 10-11.)

Two points immediately spring forward:

1) Encryption of phone communications is very uncommon. Sixteen cases of encryption out of 1,358 wiretaps is a little more than one percent. Almost no suspected criminals use voice encryption.

2) Encryption of phone conversations isn't very effective. Every time law enforcement encountered encryption, they were able to bypass it. I assume that local law enforcement agencies don't have the means to brute-force DES keys (for example). My guess is that the voice encryption was relatively easy to bypass.

These two points can be easily explained by the fact that telephones are closed devices. Users can't download software onto them like they can on computers. No one can write a free encryption program for phones. Even software manufacturers will find it more expensive to sell an added feature for a phone system than for a computer system.

This means that telephone security is a narrow field. Encrypted phones are expensive. Encrypted phones are designed and manufactured by companies who believe in secrecy. Telephone encryption is closed from scrutiny; the software is not subject to peer review. It should come as no surprise that the result is a poor selection of expensive lousy telephone security products.

For decades, the debate about whether openness helps or hurts security has continued. It's obvious to us security people that secrecy hurts security, but it's so counterintuitive to the general population that we continually have to defend our position. This wiretapping report provides hard evidence that a closed security design methodology -- the "trust us because we know these things" way of building security products -- doesn't work. The U.S. government hasn't encountered a telephone encryption product that they couldn't easily break.

The report:

http://www.uscourts.gov/wiretap02/2002wttxt.pdf

[Burce's] essay on secrecy and security:

http://www.counterpane.com./crypto-gram-0205.html#1

May 26, 2003

May 25, 2003

NW Herald Headline

From Today's Northwest Herald (McHenry County, Illinois)

Lumpen: Regime Change for US

From Issue 89 of Lumpen.

May 24, 2003

"Neen" art collective creates new "anti-copyright," "anti-IP" logo

Person of the Month for March 2003, are Rafael Rozendaal and John White C.

The most important social quest of the past century was Freedom and no other symbol has capture better the urgency of that question than the Anarchy Symbol.

The major social issue of our days, is the question of the Intellectual Property and Copyright: In a world that property and content is becoming increasingly easy to copy, shall we obey to the the old laws that will stop this illuminate re-distribution or shall we be free to copy After all, if information has any value, its because it is either a snapshot of our feelings, (songs and music), or a demo of what can become visible, (visual arts, movies etc) or a speculation on what is possible, (science) or the development of a language, (computer code), or a combination of ideas that can occur to anybody at any time ( books).

In order to bring this discussion to the multitude, Rafael Rozendaal, designed after my request, and after a suggestion by John White C. a very simple and direct logo against copyright and IP. Let's write it on all walls!

Miltos Manetas, May 2003

(via BoingBoing)

Vancouver bureaucrats are funny as hell

(via BoingBoing)

May 23, 2003

My Life With The Thrill Kill Kult - The Velvet Edge

[s] Have you completely forgotten your true mission

[s] You are under a spell that has made you forget everything.

Cry me a killer, a boy and a girl

Rise from the ashes and escape from the world

Trails of fire lace the dreams in their heads

The soft touch of desperation on The Velvet Edge

Draw down the moon on this city scum born

Where the painful sensations are mindless and torn

The absence of windows is making them stir

Tragedy chance is the Will of the Pure.

[s] "Darling!"

[s] "My treasure, come!"

[s] "At last, I've been so lonely without you."

([s] = sampled spoken words)

May 17, 2003

Ms. Vega & Me

Suzanne Vega (center) and I (on her right) in the performer's lounge at the House of Blues in Chicago, last weekend.

May 15, 2003

Matrix: Reviewed

Andrew O'Hehir (Salon) writes:

Early on in the film, Morpheus whips the inhabitants of Zion, the underground city where the last band of human rebels have their stronghold, into a frenzy. The agents of the Matrix have finally located Zion, and a dreadful army of 250,000 Sentinels -- those scary, dreadlocked killing machines from the first film -- is burrowing down through the earth, on its way to destroy the city and annihilate the free survivors of the human race. But Morpheus does not rouse the citizens of Zion for battle, although a final battle is close at hand. He wants them to party. The machines have been trying to kill them for years, decades, he reminds them, longer than anyone living can remember: "But we are still alive!"

What follows is a thunderously exciting all-night multicultural rave, an ecstatic dance party the likes of which I've never seen on film before -- intercut with a hot 'n' sweaty interlude between Neo and Trinity, who've been struggling to find some Q.T. together amid the impending apocalypse and hordes of strangers who want Neo to bless their babies. One of the marks of genuine genius in the Matrix films, I think, is the way the Wachowskis manage to have it both ways so much of the time: They can make a box-office-busting action spectacular that is also an explicit critique of media-age capitalism and a lefty-Christian parable. They can turn a sex scene between two movie stars with fabulous bodies into a celebration of the sheer sensuous delight we all share (or should share, anyway) just at being alive, experiencing the world with our own bodies and our own minds.

(via BoingBoing)

May 14, 2003

iPod used as backup for FM radio station

WFMU, an independent freeform radio station, is using an iPod as an alternate music source when the station's satellite feed fails during inclement weather, according to longtime listener Brian Redman.

"I was at the WFMU record fair Sunday and was talking to Ken Freedman, the station manager about Apple's iTunes Music Service and Macs in general," Redman told MacCentral. "In the course of the conversation he told me about the iPod at the transmitter."

WFMU broadcasts to the New York/New Jersey metropolitan area and beyond over 91.1 and WXHD 90.1 FM and Internet streaming. Their studio signal reaches their 90.1 transmitter in New York's lower Hudson Valley via satellite feed.

Station manager Ken Freedman installed a 5GB iPod at the transmitter in Mount Hope to cope with the inevitable loss of the satellite feed during the thunderstorm season. By using a phone to dial in to a remote control unit at the transmitter site, station staff can switch to the iPod instead of satellite audio. The Apple device is set on continuous random play from a playlist containing the extensive collection of "Live at WFMU" CDs (live music recorded at the radio station's studios).

"The iPod gives us the best, least expensive way of achieving audio backup for the long thunderstorm season," Freedman said. "It's a one-time expense instead of paying ISDN fixed and monthly charges. We could have used a cassette or minidisk, but that gets real repetitive since the transmitter shack is unmanned, and in thunderstorm season, we may need to employ this backup method for a few hours each month. You don't want the listeners hearing the same one-hour loop each time there's a thunderstorm. And space is at a premium also; we pay by the inch for our rack space. "

WFMU's streaming broadcast is found in the default iTunes radio list in the "Public" section. The radio station is entirely non-commercial and totally listener supported.

May 07, 2003 7:40 am

(via BoingBoing.net)

Copy Protection Is a Crime

Copy Protection Is a Crime

against humanity. Society is based on bending the rules.

Digital rights management sounds unobjectionable on paper: Consumers purchase certain rights to use creative works and are prevented from violating those rights. Who could balk at that except the pirates Fair is fair, right Well, no.

In reality, our legal system usually leaves us wiggle room. What's fair in one case won't be in another - and only human judgment can discern the difference. As we write the rules of use into software and hardware, we are also rewriting the rules we live by as a society, without anyone first bothering to ask if that's OK.

The problem starts with the fact that digital content can be copied - perfectly - from one machine to another. This has led the recording and movie industries to push for digital rights management schemes. Buy a one-time right to play the latest hit song or movie, and DRM could prevent you from playing it twice.

Of course, to exercise such exquisite control over content, DRM requires deep changes to all parts of the equation - the hardware, the operating system, and the content itself. Sure enough, some in Congress recently pushed the FCC to add a "broadcast flag" to content which digital hardware would be required to honor. DRM is barreling down the pike.

The usual criticism is that the scheme gives too much power to copyright holders. But there's a deeper problem: Perfect enforcement of rules is by its nature unfair. For contrast, consider how imperfectly rules are applied in the real world.

If your lease stipulates that you can't paint without explicit permission from your landlord, you will nevertheless patch up the scratches made by your yappy little dog on the bottom of the front door. If the high-priced industry analyst's report warns you on every page against duplicating, you'll still hand out at your weekly sales meeting copies of a page with a relevant chart. You'd snicker at the very suggestion of doing otherwise.

But why The analyst report is stamped 'DO NOT PHOTOCOPY', and the bit in your lease about not painting really couldn't be any clearer. We chuckle because we all understand that before the law there's leeway - the true bedrock of human relationships. Sure, we rely on rules to decide the hard cases, but the rest of the time we cut one another a whole lot of slack. We have to. That's the only way we humans can manage to share a world. Otherwise, we'd be at one another's throats all the time - or, more exactly, our lawyers would be at each other's throats.

Yet we're on the verge of instituting digital rights management. What do computers do best Obey rules. What do they do worst Allow latitude. Why Because computers don't know when to look the other way.

We're screwed. Not because we MP3 cowboys and cowgirls will not have to pay for content we've been "stealing." No, we're screwed because we're undercutting the basis of our shared intellectual and creative lives. For us to talk, argue, try out ideas, tear down and build up thoughts, assimilate and appropriate concepts - heck, just to be together in public - we have to grant all sorts of leeway. That's how ideas breed, how cultures get built. If any public space needs plenty of light, air, and room to play, it's the marketplace of ideas.

There are times when rules need to be imposed within that marketplace, whether they're international laws against bootleg CDs or the right of someone to sue for libel. But the fact that sometimes we resort to rules shouldn't lead us to think that they are the norm. In fact, leeway is the default and rules are the exception.

Fairness means knowing when to make exceptions. After all, applying rules equally is easy. Any bureaucrat can do it. It's far harder to know when to bend or even ignore the rules. That requires being sensitive to individual needs, understanding the larger context, balancing competing values, and forgiving transgressions when appropriate.

But in the digital world - the global marketplace of ideas made real - we're on the verge of handing amorphous, context-dependent decisions to hard-coded software incapable of applying the snicker test. This is a problem, and not one that more and better programming can fix. That would just add more rules. What we really need is to recognize that the world - online and off - is necessarily imperfect, and that it's important it stay that way.

David Weinberger () is the author of Small Pieces Loosely Joined.

(via boingboing.net)

May 09, 2003

TIBETAN MEDICINES IN DEMAND TO KEEP SARS AT BAY

WASHINGTON, May 7, 2003--Callers to Radio Free Asias Tibetan-language hotline report that Tibetans and Chinese in the Tibetan Autonomous Region are buying traditional Tibetan medicine and incense in bulk in a bid to keep the deadly SARS virus from spreading to the remote region.

Two hospital officials, who spoke on condition of anonymity, also affirmed the Chinese governments claim that no cases of SARS have been confirmed in Tibet. But several callers reported on Wednesday that dozens of people have been quarantined in Tibet with SARS-like symptoms.

"Tibetan incense, medicinal powder, and Tibetan precious pills are in great demand here, said one police officer who asked not to be named. People believe that it can prevent the virus. And SARS hasnt spread to Tibet.

Chinese officials here are also purchasing the pills, and many are sending them to China in the belief that they will protect them from this terrible disease, said another caller. In our department, all the Chinese staff members are hanging wrapped pills around their necks and sniffing them from time to time.

Some Chinese are complaining that if they put on the protective pills they fall sick. But theyre all using them--even members of the Chinese Communist Party.

Tibetan students in eastern China also report by phone that Chinese friends and acquaintances have been asking them to obtain the "rilbu gunag" pills from Tibet to help them avoid SARS.

The pills, which are black, comprise nine ingredients and prayers associated with nine medicinal deities. Many Tibetans believe these pills, which are worn around the neck and sniffed, may help prevent the spread of viruses including SARS, according to Dr. Tamding of the Tibetan Medical Center in Dharamsala, northern India.

Tibetans and Chinese in the Tibetan region are also reportedly buying large quantities of Tibetan incense to burn in their homes in an effort to ward off the SARS virus, which has sickened thousands and killed hundreds of people around the world.

A great portion of incense and pills are mailed to China. There is always a great rush at the post offices with people--both Tibetans and Chinese--sending Tibetan incense to their relatives and friends in China, one caller said.

"Rilbu gunag" pills are worn around the neck, wrapped in a yellow cloth, said one woman, a secretary in the Tibetan capital, Lhasa. In our office, all staff members, Chinese or Tibetan, were issued one wrap of Tibetan pills. Many government offices supplied these to their staff members, she said. These pills are sold by the Tibetan Medical Center in Lhasa and they cannot keep up with demand."

China's cabinet, the State Council, last week sent a fifth SARS prevention and supervision team to help local authorities prepare for the possible onset of SARS, the official Xinhua news agency reported. Tibet is one of the few places in China where no SARS cases have been confirmed.

The Tibetan Medical Center has already manufactured 140,000 such pills this year, 40,000 of which have already been sold. No comparative figures for last year were available. In Lhasa, the Tibetan Medical College and Tibetan Medical Center also manufacture the pills.

RFA broadcasts news and information to Asian listeners who lack regular access to full and balanced reporting in their domestic media. Through its broadcasts and call-in programs, RFA aims to fill a critical gap in the lives of people across Asia. Created by Congress in 1994 and incorporated in 1996, RFA currently broadcasts in Burmese, Cantonese, Khmer, Korean, Lao, Mandarin, the Wu dialect, Vietnamese, Tibetan (Uke, Amdo, and Kham), and Uyghur. It adheres to the highest standards of journalism and aims to exemplify accuracy, balance, and fairness in its editorial content. ##### 2003-05-07

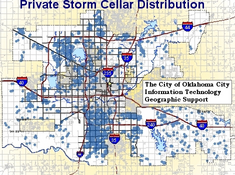

OKC: The Private Storm Shelter Location Database

The Private Storm Shelter Location database is an initiative of the Office of Emergency Management for the purpose of location trapped victims in the event of a disaster.

What type of shelters are tracked in this program

All types of privately owned shelters located within the Oklahoma City Limits. This includes any above or below ground shelter located at a private address. Publicly owned shelters intended for the general public are not tracked as part of this program.

How will this information be used by the City

In the event of a natural disaster, it is important that emergency personnel know the location of your storm shelter. With this information, emergency personnel can respond to specific locations which have storm shelters to free citizens who may be trapped.

How do I participate in this program

Request to have your shelter information included in the City's records. You can do this by calling the City at . You can also submit your shelter information online at the shelter verification page here.

Why does the City require a contact name

Contact name provides an important means to verify that all occupants of a shelter are safe. Emergency personnel find this valuable when all physical references to location, address, and owner have been removed. Such was the case during the May 3rd, 1999 tornado.

In addition to ensuring that I am on this list what other steps can I take to help rescuer find my shelter

The May 3rd, 1999 tornado taught us that it is possible for damage to be so extreme that identifying street names and house addresses can be very difficult. The City's public safety recommends that citizens have their house address number painted on the curb at their house. You can contact the City at for information on what groups provide this type of service.

NYT: Oral History Project Wants Nation of Interviewers

MICHAEL BRICK (New York Times) writes:

On this recording, Mr. Isay is making an oral history of his own family, but he is also using the interview as a trial run for a much broader project: to democratize the craft of oral history and simultaneously capture a chronicle of ordinary life in our times comparable to the body of work produced by the Works Progress Administration two generations ago.

This will turn on his ability to persuade ordinary people, starting with New Yorkers, to speak of raw workaday joy and anguish, outside their homes or neighborhood bars, in the presence of a microphone, a recording device, a friend and a stranger. It also turns on his ability to teach untrained interviewers the techniques that can elicit candid stories and unvarnished emotions.

"This is our beachhead against `The Bachelor' " Mr. Isay said, referring to the reality television show. "It's about reminding America what kind of stories are interesting and meaningful and important."

Starting in October, in Vanderbilt Hall inside Grand Central Terminal, Mr. Isay plans to build something of a quiet public confessional in the center of the motion and tumult and ordinariness of daily commuting.

Oral History Project Wants Nation of Interviewers

By MICHAEL BRICK

he voice on the recording quivers and warbles and shows the speaker's age, which is 88. The speaker is asked who he is.

"I'm Sandy Birnbaum," the voice replies. "I'm a retired biomedical scientist, have been retired for some time."

Mr. Birnbaum says that he is living a very comfortable life. But soon he will reveal things that the word "comfortable" hides everyday agonies, experienced and unspoken pretty much universally.

The questioner, David Isay, draws Mr. Birnbaum out. Mr. Isay, a grandson of Mr. Birnbaum's wife's sister, is a practiced interviewer, best known for making oral history and documentary projects broadcast on National Public Radio.

On this recording, Mr. Isay is making an oral history of his own family, but he is also using the interview as a trial run for a much broader project: to democratize the craft of oral history and simultaneously capture a chronicle of ordinary life in our times comparable to the body of work produced by the Works Progress Administration two generations ago.

This will turn on his ability to persuade ordinary people, starting with New Yorkers, to speak of raw workaday joy and anguish, outside their homes or neighborhood bars, in the presence of a microphone, a recording device, a friend and a stranger. It also turns on his ability to teach untrained interviewers the techniques that can elicit candid stories and unvarnished emotions.

"This is our beachhead against `The Bachelor' " Mr. Isay said, referring to the reality television show. "It's about reminding America what kind of stories are interesting and meaningful and important."

Starting in October, in Vanderbilt Hall inside Grand Central Terminal, Mr. Isay plans to build something of a quiet public confessional in the center of the motion and tumult and ordinariness of daily commuting.

People rushing from train to street will move past a six-by-eight-foot box of gray sheet metal wrapped in a translucent skin with a honeycomb pattern. Stopping to inspect the booth, they may push a button activating a speaker and playing aloud an edited sample oral history interview.

"If you see it from a distance, you'll see this glowing box with these car speakers," said Eric A. Liftin, an architect with Mesh Architectures in New York who was involved in designing the box. "Once you go inside, it's going to be a wood environment, totally different, what you would call warm."

Mr. Isay hopes that people will stop long enough to make an appointment to go inside, bringing a family member or friend to sit in simple wooden chairs beside a table with two microphones. In the room, a trained mediator will quickly teach them a few interviewing techniques chief among these is not interrupting then monitor recording equipment as one person interviews the other. The whole process will take three-quarters of an hour.

A copy of the recording will be made on compact disk for the participants to keep, and another copy will become part of an archive.

Another booth is planned for downtown at the Eldridge Street Synagogue, and Mr. Isay hopes to place similar booths in libraries and other public places around the country and to send a convoy of movable booths to county fairs and the like.

So far, the only financing is a $50,000 grant to Mr. Isay's nonprofit group, Sound Portraits, from the Rockefeller Foundation. But money may not be the biggest problem. Experts in the field of oral history, including some strong supporters of Mr. Isay, say that his project must overcome nonfinancial challenges to realize the scope of its ambition.

"It's oral history writ large," said Mary Marshall Clark, director of the Oral History Research Office at Columbia University and a professed admirer of Mr. Isay. She said that the project's fate rests with Mr. Isay's ability to train the mediators, who will in turn have to train the participants. "The temptation in the short form will be to get people to serve up their lives very quickly: `What was your happiest moment' "

"In truth, there's always another side," she said. "The lost dreams."

Both the product of oral history and the process of collecting it differ from journalism. Oral history describes the past, even the very recent past, while journalism describes the present. For example, this newspaper article describes the current status of Mr. Isay's project. Were it a work of oral history, this article would focus on David Isay's describing how it felt to be him and to have an office in downtown Manhattan in the early years of the new century, when he was planning a big project.

To complete the analogy to Mr. Isay's project, imagine that every day, a different person wrote the story that appeared in this space and that tomorrow it might be you.

The purpose of oral history, said Studs Terkel, the 90-year-old historian and radio interviewer who began his career with the W.P.A., is to tell the story of the world through the voices of the salt of the earth.

"Sir Francis Drake conquered the Spanish Armada," Mr. Terkel said in an interview. "I thought he did it by himself. Those who shed those other tears are what history should be about. Who built the pyramids Mrs. Pharaoh's fingernails were as manicured as Elizabeth Taylor's. Thousands of people built them. What are their stories"

Mr. Terkel said that the participants themselves are the first beneficiaries of oral history. By way of example, he said that he once interviewed a woman in a housing project who had never heard her voice on tape. When he played back the tape, the woman said, "I never knew I felt that way."

It is this part of Mr. Isay's fund-raising pitch the assertion that oral history works as therapy to the participants that draws more skepticism from experts in the field.

"We don't know really what impact this sort of recitation of life history has on individuals," said John Bodnar, a co-director of the Center for the Study of History and Memory at Indiana University.

Oral history has gone in and out of fashion since tape recorders were invented. The recent development of inexpensive duplicable compact disks and computerized recording equipment has made possible Mr. Isay's effort to democratize the interviewing in addition to the storytelling. A similar current project is the effort by the Library of Congress to collect interviews of all war veterans conducted by family members.

Professor Bodnar also questioned if participants would be forthcoming and complete. It is lies of omission, he said, that could taint the results.

"Can you imagine how many people would go out there and tell a family member with a facilitator nearby about an instance of child abuse" he said. "You're going to get the public face of these individuals more than you're going to get authentic stories."

To avoid that result, Mr. Isay plans to use the recording of his great-uncle, Mr. Birnbaum, as an example and as a training tool. As that oral document rolls along toward the 75-minute mark, where it ends, the quiver and warble in the voice grows, and pauses elongate. The voice begins to describe another side of a comfortable life, a side that has emerged since the death of the speaker's wife, Birdie Birnbaum.

"Grief is a funny thing, you know," Mr. Birnbaum says. "Right now, when I do break down, I hate to say this, but it's a good feeling. 'Cause, you know, it's like, you're God, I never thought of this before it's like you're trying to defend yourself, and all of a sudden you don't have to anymore.

"You're going to cry you know what I mean and nothing's, uh, you don't have to pretend that you're being a brave soul, gutting it through. You're just letting go, and it's a good feeling. It's hard to say, you break out crying or you choke up and you can't say a word and it's a good feeling. Yeah. You know, you no longer have to defend yourself, or act something you don't really feel, that you're happy with everything, 'cause you're not, 'cause you never will be.

"Until I get rid of that extra bed in my room. I still once in a while reach over. I don't know what to do with it.

"Oh well. That brings us up to date. That's where I am now."

On the tape, Mr. Isay asks Mr. Birnbaum whether he thought that talking about this grief might be damaging.

"Oh, no," Mr. Birnbaum says. "I'll be just back to where I was when I walked in here in about 10, 5 minutes."

May 08, 2003

DataViz: 24 Hours of US Air Traffic

From NASA, a stunning time-lapse movie showing the air-traffic over the Continental US in a 24h period. (via BoingBoing)

May 07, 2003

City of Chicago GUILTY of Covering Up Criminal Police Violence

The Chicago Anti-Bashing Network writes:

CHICAGO -- On Friday, a ten-person jury found the City of Chicago guilty of systematically covering up criminal violence by its police officers, to the point where officers felt they could commit crimes without fear of arrest or discipline by the department.

The City has said it will appeal the decision.

The wide ranging civil suit, Garcia v. City of Chicago, examined all other cases of police violence investigated by the City over a two year period, and found that in only two of the 72 cases did the City refer a case the States Attorney's office for criminal prosecution, in only one case was there an arrest, and in none of the cases did sworn police officers face employment-related sanctions such as suspensions or firings. Between 1999 and 2001, of the 135 cases where a citizen sued the police department for misconduct by its officers, the Internal Affairs Department recommended discipline in only one of them.

"If the accused is a civilian, and they know who he is and where he lives, they put the cuffs on him. But if the accused works for the police department, the accused is treated very differently," said Jon Loevy, lead attorney in the case against the City. "It is a system where off duty police officers have special protections, they are above the law, they can get away with it." Other attorneys for the plaintiff firm, Loevy and Loevy, were Mike Kanovitz and Arthur Loevy.

The landmark civil suit stemmed from the City's failure to act against one of its officers before and after the severe beating of George Garcia, 23, near the 20th District Foster station in February 2001. Officer Samir Oshana allegedly repeatedly threatened Garcia after the latter's ex-girlfriend began seeing Oshana, but continued to telephone Garcia. Garcia, however, had a photograph of Oshana showing him flashing a Latin Kings gang sign, and said he would turn the photograph over to the police if Oshana didn't cease his physical threats.

When Oshana's threats didn't cease, Garcia visited the Foster District police station on February 2, 2001 and asked that officers there take action against Oshana. That evening Oshana and another alleged Latin Kings gang member, Sargon Hewiyou, confronted Garcia and demanded that Garcia turn the photo over to them. Both flashed badges and guns, even though Hewiyou apparently is not a police officer. "I'm a fucking cop," said Oshana. "You better give me the photo or I'll fuck you up."

In front of six corroborating witnesses, Oshana and Hewiyou then punched Garcia in the face, knocking him down, and then kicked him in the face and hip. Garcia, who suffered a fractured eye orbital and nose, escaped from the beating, ran to the nearby Foster District station, and again made a report. Like many of the victims in the 72 other cases of police violence investigated by the City, Garcia vainly demanded that the police arrest one of their own.

Later that evening, Oshana's partner radioed him to let him know that Foster District police had identified Oshana as the suspected attacker. Oshana in turn telephoned his watch commander, Lt. Cohnen, who told Oshana to evade arrest. Instead of advising Oshana to turn himself in, Cohnen told him to stay at home and that if located by police or arrested, to phone Cohnen immediately. If police did not find him, Cohnen advised Oshana, "then don't worry about it."

Over the next year and half, Garcia and his family received numerous threats of violence, including death threats, from Oshana and his associates, but still police refused to arrest or discipline Oshana, until Garcia filed the civil suit naming a sergeant in the City's Internal Affairs Department (IAD).

As part of the cover-up, evidence from States Attorneys' files shows that IAD's Sgt. Joe Fivelson crudely backdated a request for prosecution to make it appear as though Garcia's suit was not what caused the City to act. However, in a supplementary report, Fivelson wrote that "the battery victim filed a Federal Civil Suit (01 C8934) which prompted contacting ASA Ann Head, Public Integrity Section for determination of possible charges." In a deposition Fivelson testified that when he heard that Oshana told Hewiyou that the police would "cover up" the fact that Hewiyou hit Garcia, Fivelson "chuckled about it" and didn't bother to ask any follow up questions.

In addition to their police being found guilty of covering up the criminal violence by officers, the City potentially faces further sanctions as the cover-up spread beyond the police department. City attorneys Darcy Proctor and Sherry Baldwin, the police's Office of Professional Standards, and their Internal Affairs Department are likely to face contempt of court proceedings. Potentially critical pages were missing from many documents ordered from the city, many were produced well after discovery, and a critical witness was withheld until the last minute. At one point Judge James Holderman angrily exclaimed to City attorneys, "I have the distinct feeling that you don't want me to review the evidence." And then when the City was caught concealing the witness, Holderman shouted at Baldwin, "Is there anything else you want to lie to me about"

The surprise witness turned out to be one Kenneth Boudreau, a Chicago police officer with one of the most notorious reputations for misconduct on the entire 13,500-member force. Boudreau once was a close associate of Lt. Commander Jon Burge, the ringleader of an infamous police torture ring at Chicago Area Two police headquarters during the 1970s, 80s and early 90s. Burge and other officers were found by Amnesty International and the city's Goldston Commission to be conducting systematic torture using electrical shock to the genitals, Russian Roulette, suffocations and burnings of dozens of African American suspects to get them to "confess" to crimes.

Boudreau's record of alleged brutality and misconduct lasted well past the Burge era. A lengthy December 17, 2001 Chicago Tribune article about Boudreau noted that

"He has obtained a [murder] confession from a man who, records show, was in jail when the murder occurred He helped to get confessions from two mentally retarded teenagers for two separate murder cases, but they both were acquitted. And he got the confession of a 13-year-old with severe learning disabilities who experts said could not understand his rights Boudreau has been accused by defendants of punching, slapping or kicking them; interrogating a juvenile without a youth officer present; and of taking advantage of mentally retarded suspects and others with low IQs."

Little substantive testimony was given by Boudreau in the trial as he is currently assigned to the Drug Enforcement Agency and the Federal Bureau of Investigation, and federal regulations prohibit federal employees from testifying in civil suits except with special permission by the Federal Marshall's office. Thanks to the last minute revelation by the City that Boudreau was a witness and employed by the DEA and FBI, it was impossible to get that permission in time for the trial. When City attorneys claimed that they didn't know of Boudreau's federal connections preventing his testimony, Holderman exclaimed that "It seems to me that the City has put its head in the sand for fear of finding out what it should know. Is it a constitutional violation or ineptitude"

Despite the City's best efforts at concealment, the Garcia v. Chicago lawsuit forced it to reveal the City's systemic failure to discipline its officers. Among the critical documents revealed was a policy memo from the Office of Professional Standards (OPS), the police agency charged with investigating alleged police misconduct. The OPS memo outlined the limited criteria under which the City would refer alleged cases of criminal police violence to the Cook County States Attorney's office for prosecution. Though even these limited criterion were routinely ignored, they were instructive as to how the City actually operates. Among the criteria for referring a case for prosecution was not necessarily the facts of the case, but whether the alleged violence was a "media case" - i.e., public pressure, or the lack of it, determined whether or not OPS allowed the incident to be criminally prosecuted.

Thanks to Garcia's lawsuit, Officer Oshana and his alleged associate in the Latin Kings gang, Sargon Hewiyou, are now under criminal indictment for felony aggravated battery in the Feb. 2, 2001 attack, and Oshana faces several counts of official misconduct. In addition to the photo which caught Oshana flashing a Latin Kings gang sign, Oshana's alleged boss in the Latin Kings gang, Ozzie Younan, posed for a photo flashing the Kings gang sign while wearing Oshana's badge hung around his neck with a gun in his lap. Oshana is also under investigation for allegedly stealing drugs from police drug busts, and giving them to his fellow Latin Kings members for resale on the street. Hewiyou is accused of impersonating an officer not only in the Feb. 2001 attack, but also in at least two other incidents at the Chromium Nightclub, 817 W. Lake Street, where he worked as a part-time bouncer.

The Chicago Anti-Bashing Network assisted George Garcia and the law firm of Loevy and Loevy by organizing court watch and publicity for the case.

www.CABN.org

Chicago Anti-Bashing Network

phone:

May 06, 2003

Ashcroft Sings

Julian Borger (from The Guardian) writes from Washington on

Monday March 4, 2002:

Since John Ashcroft became US attorney general last year, workers at the department of justice have become accustomed to his daily prayer meetings, but some are now drawing the line at having to sing patriotic songs penned by their idiosyncratic boss.

Mr Ashcroft, a devout Christian and a grittily determined singer, went public with one of his works last month, when he surprised an audience at a North Carolina seminary with a rendition of Let the Eagle Soar, a tribute to America's virtues, which continues: "Like she's never soared before, from rocky coast to golden shore, let the mighty eagle soar," and so on for four minutes.

The performance (which can be seen and heard at cnn.com/video/us/2002/02/25/ashcroft.sings.wbtv.med.html) was accompanied only by taped music, but Mr Ashcroft's staff are complaining that printed versions of the song are being distributed at meetings so that they will be able to join in.

When asked why she opposed the workplace singalong, one of the department's lawyers said: "Have you heard the song It really sucks."

A group of Hispanic justice department employees were recently summoned to see the attorney general, and went along hoping that their boss might be making a special effort to promote diversity in the department's higher ranks.

Instead, they were asked to provide a hasty Spanish lesson to give the secretary a few phrases to use on a foreign delegation the next day. The Hispanic staff were then handed printed copies of Let the Eagle Soar and asked for volunteers to translate it.

This is not the first time Mr Ashcroft's subordinates have realised that this attorney general is unlike ordinary politicians. Each time he has been sworn in to political office, he is anointed with cooking oil (in the manner of King David, as he points out in his memoirs Lessons from a Father to His Son).

When Mr Ashcroft was in the Senate, the duty was performed by his father, a senior minister in a church specialising in speaking in tongues, the Pentecostal Assemblies of God. When he became attorney general, Clarence Thomas, a supreme court justice, did the honours.

In January, a pair of 12ft statues in the atrium of a justice department building were covered by a blue curtain, on orders from Mr Ashcroft's office because the female figure Spirit of Justice was bare-breasted, and the body of her male partner, Majesty of Law, was not sufficiently covered by his toga.

The cover-up has provoked an anti-Ashcroft campaign by the singer and film star Cher, who has toured the media circuit denouncing his puritanism. She asked the Washington Post: "What are we going to do next Put shorts on the statue of David, put an 1880s bathing suit on Venus Rising and a shirt on the Venus de Milo"

Perhaps the most bizarre wrinkle in the Ashcroft enigma emerged in November when Andrew Tobias, the Democratic Party treasurer and a financial writer, published an article on his website accusing the attorney general of harbouring superstitions about tabby cats.

According to the Tobias article, advance teams for an Ashcroft visit to the US embassy in the Hague asked anxiously if there were tabby cats (or calico cats as they are known in the US) on the premises.

"Their boss, they explained, believes calico cats are signs of the devil," Mr Tobias reported.

When asked about the veracity of the report, the justice department said that it had made Mr Ashcroft laugh. There has been no further comment on the matter.

May 03, 2003

Reflections on the 25th Anniversary of Spam

While many only encountered spam (junk e-mail or junk newsgroup postings) in

the mid 1990s, my research has found it goes back much further than that.

In fact, the earliest documented junk e-mailing I've uncovered was sent May 3,

1978 -- 25 years ago last Saturday. (It was written May 1 but sent on

May 3.) And in a surprising coincidence (*),

just a month ago marked the 10th anniversary of March 31, 1993, the first

time a USENET posting got named a spam.

(Note: You can hear me (briefly) interviewed about this anniversary on

the May 2 edition of NPR's "All Things Considered.")

While many only encountered spam (junk e-mail or junk newsgroup postings) in

the mid 1990s, my research has found it goes back much further than that.

In fact, the earliest documented junk e-mailing I've uncovered was sent May 3,

1978 -- 25 years ago last Saturday. (It was written May 1 but sent on

May 3.) And in a surprising coincidence (*),

just a month ago marked the 10th anniversary of March 31, 1993, the first

time a USENET posting got named a spam.

I learned of that first spam through a report from Einar Stefferud who read

a history

I prepared of the term "spam" and how the name of the canned ham became our

name for junk e-mail. I had original set out to research the history of

the term, but it became impossible not to research a bit of the history

of the act.

That first spam was sent by a marketer for DEC - Digital Equipment Corporation.

Today, you may not know DEC, since it was bought by Compaq and is now a unit

of HP, but in those days it was the leading minicomputer maker, and its

computers provided the platform for the development of Unix, C and much of

the internet, to cite just a few minor events.

By 1978 the Arpanet (as the internet was then known) had already provided

network E-mail to a large number of folks at universities, government

institutions and universities for over 6 years. E-mail was the biggest source

of traffic on the Arpanet. A few years prior, Dave Farber had created

"MsgGroup," the first network mailing list. (Though Plato and other

timesharing systems had laid the foundations for online community and

conferencing some years before that.)

The DEC marketer, Gary Thuerk, identified only as "THUERK at DEC-MARLBORO"

(There were no dots or dot-coms in those days, and the at-sign was often

spelled out) decided to send a notice to everybody on the ARPANET on

the west coast. In those days there was a printed directory of everybody

on the Arpanet which they used as source for the list.

The message trumpeted an open house to show off new models of

the Dec-20 computer, a foray into larger, almost mainframe-sized systems.

This was a spam, though the term would not be used to refer to it for

another 15 years. Thuerk had his technical associate, early DEC

employee Carl Gartley, send the message from his account after several edits.

Alas, at first he didn't do it right. The Tops-20 mail program would only

take 320 addresses, so all the other addresses overflowed into the body of

the message. When they found that some customers hadn't got it,

they re-sent to the rest.

As you can guess there was quite a response, with (as is typical) far more

volume of debate than actual spam. It's amusing to see that one

future celebrity --

a young free software guru Richard Stallman -- at first wondered why people

were so upset about the message. He later said the mistaken placement of

all the addresses into the body did bother him, but he gets the dubious

honour of being perhaps the first spam defender. Of course like all of us

he was 25 years younger and the problem was brand new.

In those days the Arpanet had an official "acceptable use policy" which

limited it to use in support of research and education. So this message

was a pretty clear violation, and the DCA, which ran the Arpanet, gave

a very stern call to Thuerk's boss about the matter.

The policy was well enough known over time that we would not see significant

spam for many years to come after that.

More detailed history

You can read my history of the term spam and

how it came to mean abuse of the net.

You can also just go directly to the spam and

the reaction to it, as well as more from my recent conversation with

Gary Thuerk. You can also go directly to Stallman's defence of spam.

This site contains a number of essays on the spam problem, which I have

been studying for many years, trying to find solutions which don't destroy

the core values embodied in the mail system. In spite of what some may feel,

we wanted a extremely cheap e-mail system where anybody could mail anybody,

which protected anonymous communication and fostered values like free speech,

the ability to do unsolicited communication. Those are not bugs, so fighting

spam while keeping those values, along with other core social goals,

is a delicate task.

You can read my current best plan to end spam if

your interests lie that way. Other essays can be found at my

spam essay page.

Escalation of the battle

Spam fascinates me because it sits at the intersection of three important

rights -- free speech, private property and privacy. It's also the first

major internet governance issue (possibly in tandem with DNS) that the

members of the internet community have been so deeply concerned with.

The reaction to it has been remarkable. By attacking something we hold

dear, and goading us by using our own tools and resources to do it, spam

generates emotion far beyond its actual harm, even though that

actual harm is quite considerable.

Spam pushes people who would proudly (and correctly) trumpet how we

shouldn't blame ISPs for offensive web sites, copyright violations and/or

MP3 trading done by downstream customers to suddenly call for blacklisting of

all the innocent users at an ISP if a spammer is to be found among them.

People who would defend the end-to-end principle of internet design eagerly

hunt for mechanisms of centralized control to stop it. Those who would

never agree with punishing the innocent to find the guilty in any other

field happily advocate it to stop spam. Some conclude even entire nations

must be blacklisted from sending E-mail.

Onetime defenders of an open net

with anonymous participation call for authentication certificates on every

E-mail. Former champions of flat-fee unlimited net access who railed against

proposals for per-packet internet pricing propose per-message

usage fees on E-mail. On USENET, where the idea of canceling another's

article to retroactively moderate a group was highly reviled, people now

find they couldn't use the net without it. Those who reviled at any attempt

to regulate internet traffic by the government loudly petition their

legislators for some law, any law it almost seems, against spam. Software

engineers who would be fired for building a system that drops traffic on

the floor without reporting the error change their mail systems to silently

discard mail after mail.

It's amazing.

Dozens of anti-spam companies have sprung up in the past few years, offering

a range of solutions including content-based filtering, blacklists,

collaborative filtering, spamtrap detection and removal, e-stamps and

some bulk detection. Remarkably, one new company called Habeas (trying an

)

is selling not a spam-blocking service, but a magic trademarked term that

will let legitimate mailing list owners get past the collateral damage caused

by existing spam-blocking tools. Their product is to get you past the

spam filters.

Attempts to nail down a definition of spam seem to always end in quagmire.

Each party to the debate seems determined to make sure that everything

they think is spam be included in the definition, lest one spam slip through,

but of course also keen that nothing they don't think is spam be blocked.

Reconciliation seems near impossible.

The solutions

Here's a brief summary of some of the current active methods and proposals

and how effective they are.

Content-based filters

Filters have a big advantage because they only need to be installed at the

receiver. Some of the latest filtering tools, like SpamAssassin and the

latest Bayesian algorithms are doing quite well in terms of the amount of

spam they stop. However, they all have "false positives" which means they

falsely identify real mail as spam, and block it. Most filters have no

way to identify that mail was sent in bulk (the core requirement to spot

a spam) and thus must rely on finding common patterns used by spammers.

The hand-tuned filters need regular updating by people. The learning filters

adjust automatically but only by letting some spam through.

In terms of effectiveness, these are 2nd only to challenge/response tools.

Blacklists

There are many competing blacklists, some of strong ethics, others more

dubious. Nonetheless all rely on blocking mail from accused or confirmed

spammers, with debate over the standards of proof and the definitions of

spam. Some have gone so far as to blacklist entire ISPs or even nations.

Almost everybody who runs a mail server, it seems, has a story about getting

on a blacklist and having to figure out how to get off, if they were able to.

Blacklists certainly do scare ISPs, and the blacklisting of open relay servers

had, over the course of many years, done a lot to get people to close up

their relays (at the cost of making it harder for roaming users to send

E-mail.)

Collaborative filters

These filters, such as Vipul's Razor (now via CloudMark) rely on the first

poor souls who get a spam reporting it to a central server. As the reports

come in, the spam can be identified and rules can be written to block it.

These are reasonably effective, and go after bulk, which is good. They have

fewer false positives if done well. They are very similar to...

Spamtrap filters

These are primarily used by BrightMail Inc., which is probably the largest

commercial anti-spam operation. Brightmail maintains huge numbers of

addresses seeded onto spammer lists. When messages arrive, they are almost

surely spam, and human beings look at them to derive rules to filter out and

retroactively delete the messages. Very few false positives, but

unfortunately reportedly only about 60-70% effective.

Challenge/Response

Dear to my heart because to the best of my knowledge, I wrote the first of

these, a never-productized program called Viking-12. These tools know all your existing

contacts, and when they receive mail from a new correspondent, they send

out a "challenge" E-mail that asks the mailer to do something to confirm

they are a real human being and not a spammer. When they do, the held

mail is automatically delivered and they are on the good list from then on.

These tools are extremely effective; only a few spammers ever respond to the

challenges. However, for various reasons some legitimate correspondents

also don't response, so it is necessary to browse the list of messages that

never got a response to quickly search for the real messages. However, they

are few, and they usually have low spam scores when used in combination with

filtering tools. This can get the false positive rate extremely low.

Challenge/response without scanning the non-respondents blocks anonymous

mail.

Today several companies offer them, and there are free software projects

like TDMA which perform this function. A number of research projects have

developed what could be termed "Turing tests" for the challenges, to assure

that the respondent is a human being.

ISP bulk detection

A number of large ISPs, AOL in particular, have their own spam detectors

which rely on the fact that due to their size, they have so many addresses

that any spam attack is sure to arrive multiple times. They can thus detect

these and get rid of them. A good approach, but past history shows some

nasty false positives, with ordinary mailing lists being blocked for their

volume. One notorious case involved AOL blocking acceptance letters from

Harvard, which were sent out as a highly desired mass mailing.

This is a worthwhile technique but needs to be done with more care. Today's

collateral damage is too high.

Spam-banning laws

There have been may proposed anti-spam laws, and indeed around half of

all U.S. states have such laws -- California has two! While most of

these state laws will eventually be declared unconstitutional since it is

important that states not have the power to regulate something as

geography independent as E-mail, what can't be disputed is that they are

having essentially no effect. There have been very few prosecutions under

them, and spam levels continue to increase tremendously. Some hold out

more hope for a U.S. federal law, however an increasing percentage of spam

comes from overseas. Advocates hope that even overseas spam can be stopped

by a federal law if a U.S. connection can be found. Fellow EFF board member

Larry Lessig advocates that a law which pays a bounty to those who hunt

down the U.S. connection on any spam without a mandatory label could do the

trick.

Torts

There's been a fair bit of success against big institutional spammers in

tort law. AOL and other companies have sued spamming companies using a

variety of torts to shut them down. So far, alas, like Whack-a-moles, other

spammers keep coming up. However, there have also been disturbing trends

in the tort area. For example, Intel has sued an ex-employee who spammed

Intel's entire employee base with his grievances against the company using

a legal doctrine called "trespass to chattels." Unfortunately, the

consequences of declaring E-mail to be trespass are even nastier than spam.

A large number of spams are already illegal, of course, amounting to

confidence tricks or illegal selling of prescription drugs. Some of those

laws are being used against the spammers too.

Opt-out lists

Recently, a federal do-not-call list was instituted in the USA to stop phone

spam. Unfortunately, doing the same for E-mail

is difficult and faces the same problems all laws would.

Hiding your address

The most common technique today seems to be hiding your E-mail address so

that it can't be harvested by spammers. Unfortunately, by using dictionary

attacks, they are managing to spam people who have never exposed their

E-mail in public. I consider this desire to never reveal your E-mail

one of the greatest damages done by spammers, so I don't view hiding as

a great solution to the problem.

Vigilante attack

Some anti-spammers have resorted to harassment and even extra-legal

efforts against spammers. They make a great tale to tell, but so far do

not seem to be stemming the tide. And they have all sorts of nasty

backbite, since they amount to sinking to or below the level of the enemy.

Up and coming solutions

E-Stamps

This idea is regularly re-generated.

I first proposed it myself back in 1995 and later

came to reject it. The idea is to put some low (or routinely not collected)

cost on sending an E-mail that does not bother ordinary senders, but stops

spam from being cost-effective. It has many advocates, and might work

if it could be universally adopted. However, it suffers from a "you can't

get there from here" problem. Until people are offering stamps with their

E-mail, you can't demand them, and they have little incentive to offer them

if nobody is demanding them. This technique could only be built by

piggybacking on other techniques, such as doing challenge/response and offering

stamps as a means to bypass the challenge.

Throttling bulk volume from unaccountable addresses

My current favoured proposal, detailed here.

Authentication

A number of people on anti-spam lists propose putting an authentication

regime into E-mail, to the extent that one could refuse mail that was

not digitally signed or otherwise verifiable. This would stop forging

return addresses or the use of non-existent return addresses. A number

of laws also address this.

Such schemes unfortunately abandon the longtime goal of an open E-mail system

without central management (such as a certificate authority) which allows

anonymous speech.

The Future

The spam problem will get worse before it gets better. Spammers will

try new and nastier techniques to get around the blockers, and the blockers

will try new and improved technologies. Spammers are already moving to

even nastier techniques, such as using worm programs, or exploiting windows

in widely deployed software systems to take over other people's machines and

get them to do the spamming. It is rumoured that some spammers are using

some of the wide number of open wireless networks to drive up to a building

and spam using the network inside. Such tactics can't be countered

with blacklists, for example, though they are fortunately highly illegal.

However the spam problem is solved, or partially solved, it will remain

fascinating as the internet community grapples with its first serious

abuse issue from within. Most other abuse issues have involved outsiders,

ranging from the religious conservatives trying to ban smut to the RIAA trying

to stop file-sharing, trying to regulate the net. Spam has caused the

network insiders themselves to seek to regulate it.

This is important because it will, of course, not be the last such issue.

How we manage ourselves here will be an indicator of things to come.

I hope that as we do this we will remember the principles that make free

societies free, and the principles upon which the internet was built.

End-to-end, open designs. The ability for anybody to communicate with

anybody, even without an invitation. Ubiquitous, deliberately low-cost

communications that are not accounted for on a packet-by-packet basis.

In addition, we must realize that though all internet traffic flows over

private property, this does not mean we should forget constitutional

principles like the U.S. 1st amendment. As I view it, the 1st amendment

isn't just the law, it's a good idea. We owe a duty to preserve the

values it contains -- and the long history of how to protect them that

is embodied in 1st amendment jurisprudence -- as we architect the communications

systems of the future. For in building and regulating the internet,

we are doing no less than creating the primary platform for speech and

the press of the new century.

That is not a task to be taken lightly.