Sun 7 May 2006

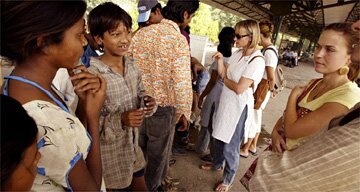

Foreign tourists are introduced to street children at New Delhi railway station. Photograph: Amit Bhargava/Corbis

The Observer, reports:

Clearing his throat theatrically as he gets ready to reveal a highlight of the tour, group leader Javed stops halfway up the staircase to platform one and points through the railings to a dark alcove beneath the footbridge over the tracks.

‘This is where the street children sleep,’ he says, smiling at the cluster of tourists who are craning forward to hear his voice above the roar of the trains below. A small boy climbs out from the hole, steps across the corrugated iron roof and balances himself on a ledge on the other side of the bars, staring back at the visitors, perplexed.

The tourists pause for a while taking in his malnourished appearance, his filthy clothes and glazed eyes. The boy doesn’t say anything, but Javed briskly explains that this child, like a lot of the homeless children who live in New Delhi railway station, is addicted to a white correction fluid, called Eraz-Ex.

Most carry a small square of cloth soaked in the chemical, which they hold to their noses and inhale periodically. ‘They spend more than half the money they earn from selling rubbish they find on the platform on buying it from the stationary stalls in the market,’ he says. ‘It does make them a bit violent.’

He pauses to give the group of visitors from Australia, Russia and England a chance to ask questions, before running through the advantages of sleeping in the gap between the platform roof and the walkway. It’s shady and you have to be small to get to it, which makes it relatively safe from the station police. But there are the overhead electricity wires to look out for. ‘Several of the children have been electrocuted by that wire,’ he adds.

For anyone weary of Mughal tombs and Lutyens architecture, a new tourist attraction is on offer for visitors to the Indian capital: a tour of the living conditions endured by the 2,000 or so street children who live in and around Delhi’s main railway stations. For two hours, tour guides, themselves former street children, show visitors what life is like for the city’s most deprived inhabitants.

The money raised (200 rupees a ticket - £2.50) goes to a well-respected local charity which tries to rehabilitate these children. The trip is designed as an awareness-raising venture and organisers deny that this is the latest manifestation of ‘poorism’ - voyeuristic tourism, where rich foreigners come and gape at the lives of impoverished inhabitants of developing countries. Bus tours of the shanty towns of Soweto or guided walks through the slums of Rio have attracted curious tourists for many years; the visit to Delhi’s railway underworld has been running for just a few months but has already proved popular with Western and Indian visitors.

‘We’ve come to educate ourselves about these homeless children who live near us. Most of the time people ignore them; I think it’s good to pay them some attention,’ an Indian post-graduate student in the group says.

The tour guide instructs visitors not to take pictures (although he makes an exception for the newspaper photographer). ‘Sometimes the children don’t like having cameras pointed at them, but mostly they are glad that people are interested in them,’ Javed claims, adding that the friendly smiles of the tourists are more welcome than the railway policemen’s wooden sticks and the revulsion of the train travellers. He hopes the trip will get a listing in the Lonely Planet guides. Nevertheless there is something a little uncomfortable about the experience - cheerful visitors in bright holiday T-shirts gazing at profound misery.

Next up is the railway medical centre where a queue of half a dozen children is waiting to see a young doctor. Wearily she lists the problems the children face - broken limbs from collision with the trains or from falling off moving carriages as they go about their work gathering discarded plastic water bottles, injuries from the beatings meted out by the station police, malnutrition, tuberculosis.

‘Do you see a lot of unwanted pregnancies?’ one tourist asks. ‘What kind of accidents do you see?’ The questions keep coming. Eventually the doctor points out that she has to give her attention to the boy slumped weakly in front of her desk. ‘There are a lot of patients waiting,’ she says firmly and the group is ushered out.

The tour moves swiftly on to a secluded train siding, where around 15 children are sitting on a carpet, each with a small blackboard, helped by a volunteer to write a few letters and numbers. These are children who live with their families in the tents and shacks around the station. Their parents have brought them to the capital to escape desperate rural poverty. Protected by their relatives from the harshest violence of street life, these children are better off than the orphans who sleep on the station roof, but life remains a battle against hunger.

This school is run by the Salaam Baalak Trust, which is the organisation behind the tourist trips. There doesn’t appear to be much formal teaching going on, but the children seem happy to be grouped in this quieter stretch of the station, under adult supervision.

Javed explains how each platform is controlled by a gang leader, one of the older street children, who protects and menaces the other boys in his care. Shouting to make himself heard above the rumbling of the trains, our guide explains that children who run away from home - escaping alcoholism, poverty, natural disasters and family violence - usually take the train to Delhi. Gang leaders spot a new arrival as soon as he steps off the train and offer help with finding food and safe places to sleep.

New arrivals are shown how to strap sharp blades to their index fingers for slashing pockets; they learn which fruit-juice sellers will protect them and where to sell the plastic bottles and silver foil picked from the carriage. Their day’s takings are taken by the gang leader who redistributes the money (although not all of it) on Saturday, when the children take a day off to watch Bollywood movies. Platform one, where the luxury tourist trains stop, is the most heavily policed area, but also the most lucrative fiefdom, and street children are skilled at dodging trains to crawl into the carriages from the other side. There are no girls in the gangs because they are picked up by pimps as soon as they arrive, Javed explains.

By the end of the walk, the group is beginning to feel overwhelmed by the smells of hot tar, urine and train oil. Have they found it interesting, Javed asks? One person admits to feeling a little disappointed that they weren’t able to see more children in action - picking up bottles, moving around in gangs. ‘It’s not like we want to peer at them in the zoo, like animals, but the point of the tour is to experience their lives,’ she says. Javed says he will take the suggestion on board for future tours.

To see how the children work the trains, you must arrive just after dawn, when the night trains arrive one after the other, full of discarded junk. Small packs of children, aged between seven and 14, drag huge sacks behind them picking up any litter that can be sold. On a stretch of abandoned track, 100 metres away from the platforms they sort through their findings - snatched purses and half-eaten train meals among the rubbish.

Babloo, who thinks he is 10, has been living here for maybe three years. His hands are splashed white from the correction fluid that he’s breathing in through his clenched left fist, and he pulls a dirty bag filled with bottles with his other hand. His life is unrelentingly bleak and he recognises this. ‘I don’t know why people come and look at us,’ he says.

For details of the tours email , call Javed on or see www.salaambaalaktrust.com.

See how the other half lives

Rio De Janeiro

There are 750 favelas in Rio, which are home to 20 per cent of the city’s population. While tourists are not advised to wander into these hillside shanty towns unaccompanied, walking tours of some of the safer neighbourhoods are available, which will give tourists a fascinating insight into favela life. Some of the tours include visits to community projects and health centres. A three-hour tour of the Vila Canoas and Rocinha favelas is available from Favela Tour (; www.favelatour.com.br).

Soweto

You can stay in a bed and breakfast in the Johannesburg township of Soweto, where nine ethnic groups live peacefully together. The township was featured recently in the film Tsotsi, and visitors should see shacks, hospitals and the Nelson Mandela museum, while their money helps to regenerate the area. Day tours plus overnight stay are £95 with the Soweto B&B Association. Trips can be booked as part of longer itineraries with Rainbow Tours (020 7226 1004; www.rainbowtours.co.uk).

New York

The streets of the Bronx and East Harlem districts of NYC are known for high levels of unemployment, crime and a disadvantaged and alienated population. But with their mix of Puerto Ricans, Irish, Italians and Afro-Americans they have also given birth to a rich culture and many important genres of music. A tour traces the area’s story through its musical roots. Spots relating to the origins of mambo, ska, soul and hip-hop are included. From around £8 for a couple of hours, details from 00 1 ; www.thepoint.org.

Belfast

A driver will offer an in-depth commentary while driving you round the areas of Belfast affected by the Troubles on a Black Taxi Tour (028 9030 1832; www.belfastcityblacktaxitours.com). Shankill and Falls Roads, the peace line dividing the Protestant and Catholic areas, the famous murals and the main city sites are included. It costs £25 for two people.

Rotterdam

About half of Rotterdam’s population is from, or has a parent from, outside the Netherlands. Residents will welcome you into their homes, shops, cafes and places of worship on a tour of the deprived ethnic areas, including the predominantly Muslim Spangen. City Safari Tours (010 436 35 67; www.citysafari.nl) arranges tours for £32 per person. These are unguided, but you get a map showing the places to stop and meet the locals.